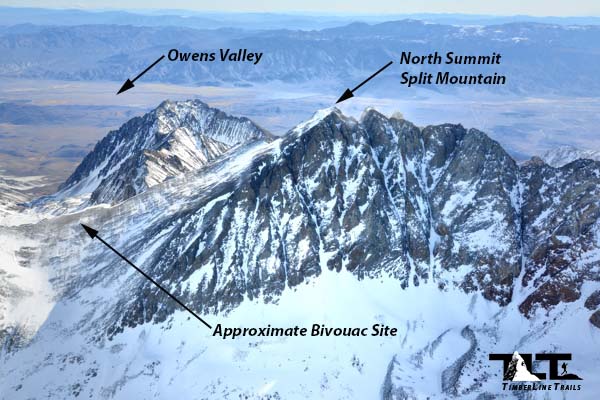

Split Mountain - rises 14,058 Ft above sea level, and makes up part of the spectacular eastern escarpment of the Southern Sierra Nevada located in the U.S state of California. The peak derives it's name from two steep gullies that divide the center of the mountain. When both gullies meet at the top of the peak, they create an obvious notch known as the split. Thus the name, Split Mountain. Though there are several routes to the summit, we choose the Eastern Approach via Red Lake. This route requires a four wheel drive vehicle to access the trailhead, which is located on the desert floor. From there, a not so well maintained trail leads you up a steep canyon that ends at Red Lake. The trail ends at Red Lake, and the climber must then continue cross country to a Class 3 gully that tops out on a large upward sloping section that will eventually get you to the summit.

I have to start off by saying that things do not always go well when climbing mountains and on this particular trip I ended up getting frostbite due to a cold night out on that large upward sloping section mentioned above. Below is an account of our trip up Split Mountain in 2002.

Summit Fever on Split Mountain -

It was early October, and we were looking forward to scratching off another 14,000 foot peak from our list of peaks to climb. Our destination was Split Mountain, which is located in the Palisade region of the California Sierra Nevada. The climbing party consisted of my son Sean, Mike (longtime friend and climber), Matt (a friend of Sean) and Tom (a recently acquired friend and climber). Having climbed several peaks of greater difficulty in the past, I was unconcerned about Split Mountain, and figured that an easy summit would be the order of the day. Sean begged to differ and expressed concern over climbing above 14,000 feet in October. His concern was the unpredictable weather conditions in the Sierra at that time of year. My wife agreed, but their warnings went unheeded. I simply told them that Split Mountain was not a big deal, and that Sean should get busy organizing his pack. We embarked on our journey late afternoon, October 3, 2002, and arrived in the small town of Lone Pine that night. Traveling about 13 miles upslope we discovered a small campsite located at around eight thousand feet, and decided to spend the night there. From previous experience, I have found that an initial night between seven and ten thousand feet is very helpful when it comes to preventing the undesirable effects of altitude sickness. Laying out our sleeping bags, we prepared for the night. Mike wanting to catch up on current events, utilized his headlamp to read the newspaper before calling it quits for the day.

Traveling about 13 miles upslope we discovered a small campsite located at around eight thousand feet, and decided to spend the night there. From previous experience, I have found that an initial night between seven and ten thousand feet is very helpful when it comes to preventing the undesirable effects of altitude sickness. Laying out our sleeping bags, we prepared for the night. Mike wanting to catch up on current events, utilized his headlamp to read the newspaper before calling it quits for the day.

When the sun arose the next morning, we caught our first glimpse of the surrounding slopes. Mike and I were surprised to see the amount of freshly fallen snow, but concluded that it was only a light dusting, and not enough to present any difficulties for our intended climb. Sean, on the other hand, had a different perspective. He took me aside and warned me that although the snow appeared to be minimal, it could prove to be a significant problem at higher elevations. I responded by telling him not to worry and to just take things as they come.

I have to start off by saying that things do not always go well when climbing mountains and on this particular trip I ended up getting frostbite due to a cold night out on that large upward sloping section mentioned above. Below is an account of our trip up Split Mountain in 2002.

Summit Fever on Split Mountain -

It was early October, and we were looking forward to scratching off another 14,000 foot peak from our list of peaks to climb. Our destination was Split Mountain, which is located in the Palisade region of the California Sierra Nevada. The climbing party consisted of my son Sean, Mike (longtime friend and climber), Matt (a friend of Sean) and Tom (a recently acquired friend and climber). Having climbed several peaks of greater difficulty in the past, I was unconcerned about Split Mountain, and figured that an easy summit would be the order of the day. Sean begged to differ and expressed concern over climbing above 14,000 feet in October. His concern was the unpredictable weather conditions in the Sierra at that time of year. My wife agreed, but their warnings went unheeded. I simply told them that Split Mountain was not a big deal, and that Sean should get busy organizing his pack. We embarked on our journey late afternoon, October 3, 2002, and arrived in the small town of Lone Pine that night.

Traveling about 13 miles upslope we discovered a small campsite located at around eight thousand feet, and decided to spend the night there. From previous experience, I have found that an initial night between seven and ten thousand feet is very helpful when it comes to preventing the undesirable effects of altitude sickness. Laying out our sleeping bags, we prepared for the night. Mike wanting to catch up on current events, utilized his headlamp to read the newspaper before calling it quits for the day.

Traveling about 13 miles upslope we discovered a small campsite located at around eight thousand feet, and decided to spend the night there. From previous experience, I have found that an initial night between seven and ten thousand feet is very helpful when it comes to preventing the undesirable effects of altitude sickness. Laying out our sleeping bags, we prepared for the night. Mike wanting to catch up on current events, utilized his headlamp to read the newspaper before calling it quits for the day.When the sun arose the next morning, we caught our first glimpse of the surrounding slopes. Mike and I were surprised to see the amount of freshly fallen snow, but concluded that it was only a light dusting, and not enough to present any difficulties for our intended climb. Sean, on the other hand, had a different perspective. He took me aside and warned me that although the snow appeared to be minimal, it could prove to be a significant problem at higher elevations. I responded by telling him not to worry and to just take things as they come.

Repacking our sleeping bags, we returned to the city of Lone Pine where we picked up a backcountry permit and had breakfast at a local cafe (photo to the left). After breakfast, we continued our travels north to the city of Big Pine where we turned west toward the foothills of Split Mountain.

Repacking our sleeping bags, we returned to the city of Lone Pine where we picked up a backcountry permit and had breakfast at a local cafe (photo to the left). After breakfast, we continued our travels north to the city of Big Pine where we turned west toward the foothills of Split Mountain.Mike's four wheel drive did a great job negotiating the rough dirt road that led to the trailhead (photo to the right), and we arrived at a small flat spot on the upper desert slopes of the Owens Valley at about mid morning. I knew that the climb to the top of Split Mountain involved a low start, but the contrast between the snow capped peak and the desert sagebrush presented a vivid picture of what was to come. Strenuous work! The guide book only added to this perception of upcoming hardship by describing the approach as a poorly maintained steep trail.

After a couple of hours working our way up the path, I formed the opinion that it wasn't so bad. All it took was a slow and steady pace to get to Red Lake, and we had plenty of time to spare once we got there. The greatest surprise turned out to be the three or four climbing parties already situated in the area. This was unexpected due to the remote location and the time of year.

After a couple of hours working our way up the path, I formed the opinion that it wasn't so bad. All it took was a slow and steady pace to get to Red Lake, and we had plenty of time to spare once we got there. The greatest surprise turned out to be the three or four climbing parties already situated in the area. This was unexpected due to the remote location and the time of year.Mike and Tom had bivy sacks that required very little clear space for set up, and this allowed them to find spots fairly quickly. Sean and Matt having a good sized two man tent, searched the north end of the lake and found a large flat rock that proved adequate for their needs. I was carrying a small two man tent and found a location a few yards away.

My site, however, required the removal of a couple of embedded rocks in order to make it more suitable for occupancy so I used one of my trekking poles for the job and ended up breaking off it's tip trying to dislodge a stubborn rock. After the lesson in the proper use of equipment, I ate some freeze dried food and retired for the night.

The next morning, I prepared for the day by downing a couple of pop tarts and putting a few small items in my summit pack. It didn't take long for the rest of our group to assemble, and we left camp for the summit at around 6:30AM. The first couple hundred feet of elevation gain went well, but progress slowed substantially when we encountered loose scree mixed with powdery snow. This required a balancing act just to stay on ones feet.

Deep pockets of snow also added to the difficulties and required jumping from one rock to another in order to avoid sinking in the snow between the rocks. Care had to be taken on every maneuver so as not to jamb a leg between opposing rocks. I had come across a climber in the past whose friend had broken a leg doing just that, and with that in mind, I carefully planned each jump.

Deep pockets of snow also added to the difficulties and required jumping from one rock to another in order to avoid sinking in the snow between the rocks. Care had to be taken on every maneuver so as not to jamb a leg between opposing rocks. I had come across a climber in the past whose friend had broken a leg doing just that, and with that in mind, I carefully planned each jump.

As we continued, the gentle slope soon gave way to a steep chute consisting of jumbled rock and snow. Not having a rope, extreme caution had to be exercised at all times. Accumulated snow and ice were present on nearly every ledge, and a potential fall was a continuous concern. The slippery class three sections near the top were particularly precarious. Tom and Mike were the first to exit the section, and the rest of us joined them shortly after. One of the other climbing parties consisting of a man and his two sons had already passed us, and they were making their way up the northern slope of the mountain.

Six other climbers, whom we had spotted on the way up, ended up turning back before reaching the top of the cirque. Under dry conditions the trip to the summit would have been an easy task, but the entire approach was covered in snow, making upward movement difficult at best. Tom took the lead but after thirty to forty five minutes of work, decided to turn back. He calculated that the time spent gaining the last two hundred feet was prohibitive and figured that a night out in the open, which he was not prepared to do, would be the result of continuing on. Matt after listening to Tom's reasoning decided to turn back with him. He had been battling a headache all day, and figured that base camp would be a much better place to recover. Sean was considering it too, but Mike and I were not.

Deep pockets of snow also added to the difficulties and required jumping from one rock to another in order to avoid sinking in the snow between the rocks. Care had to be taken on every maneuver so as not to jamb a leg between opposing rocks. I had come across a climber in the past whose friend had broken a leg doing just that, and with that in mind, I carefully planned each jump.

Deep pockets of snow also added to the difficulties and required jumping from one rock to another in order to avoid sinking in the snow between the rocks. Care had to be taken on every maneuver so as not to jamb a leg between opposing rocks. I had come across a climber in the past whose friend had broken a leg doing just that, and with that in mind, I carefully planned each jump.As we continued, the gentle slope soon gave way to a steep chute consisting of jumbled rock and snow. Not having a rope, extreme caution had to be exercised at all times. Accumulated snow and ice were present on nearly every ledge, and a potential fall was a continuous concern. The slippery class three sections near the top were particularly precarious. Tom and Mike were the first to exit the section, and the rest of us joined them shortly after. One of the other climbing parties consisting of a man and his two sons had already passed us, and they were making their way up the northern slope of the mountain.

Six other climbers, whom we had spotted on the way up, ended up turning back before reaching the top of the cirque. Under dry conditions the trip to the summit would have been an easy task, but the entire approach was covered in snow, making upward movement difficult at best. Tom took the lead but after thirty to forty five minutes of work, decided to turn back. He calculated that the time spent gaining the last two hundred feet was prohibitive and figured that a night out in the open, which he was not prepared to do, would be the result of continuing on. Matt after listening to Tom's reasoning decided to turn back with him. He had been battling a headache all day, and figured that base camp would be a much better place to recover. Sean was considering it too, but Mike and I were not.

I agreed that progress had been slow, and that a bivouac was a real possibility, but felt confident that we could endure a night out in the open if necessary. Summit fever had set in, and making the peak had become my primary focus. Split Mountain had to be conquered, no matter what, and I explained to my son Sean that coming back and redoing the climb was not an option for me, and encouraged him to finish what we had started.

I agreed that progress had been slow, and that a bivouac was a real possibility, but felt confident that we could endure a night out in the open if necessary. Summit fever had set in, and making the peak had become my primary focus. Split Mountain had to be conquered, no matter what, and I explained to my son Sean that coming back and redoing the climb was not an option for me, and encouraged him to finish what we had started.I reasoned that he was in no danger and was sufficiently dressed for the cold. He had three layers of fleece and a complete Gortex shell in his possession, whereas my outer clothing consisted of two layers of fleece and a Gortex shell. Mike, on the other hand, had only a single layer of fleece and no waterproof/windproof shell. This concerned me. A few months ago, I convinced Matt and Sean to get lightweight (space blanket style) bivy bags just in case of a predicament like this. Fortunately, they had them along. Those items would prove essential for what was to come.

The only other emergency shelter in our possession was a cheap dime store space blanket that I was carrying. After taking this mental inventory I asked Matt, due to the fact that he was going down, if he would be willing to part with his bivy sack and headlamp for the sake of Mike. He immediately agreed, and with those pieces of equipment I figured we were good to go. Shortly after saying our goodbyes we noticed the two boys coming down without their father. They had failed to make the summit and were wasting no time in descending. We had a short conversation with them, and learned that they were heading for the notch in order to wait for their father's return. We were not discouraged by their decision to turn around, and we continued to push ahead, but deep snow continued to plague us.

Sometime later, we noticed the man who had separated from his boys on his way down. He had made the summit and was in a hurry to rejoin them. He told us that the summit was not far off and with a bit more work, we too would be on top. This proved to be true and in an hour or so, all three of us were standing on the summit. Wanting to record our success, we began digging in the snow for the summit register.

Sometime later, we noticed the man who had separated from his boys on his way down. He had made the summit and was in a hurry to rejoin them. He told us that the summit was not far off and with a bit more work, we too would be on top. This proved to be true and in an hour or so, all three of us were standing on the summit. Wanting to record our success, we began digging in the snow for the summit register.Daylight was vanishing, we had to give up looking for the summit register. There was simply no time for a thorough search. A couple of photographs (image to the left shows Mike and Sean on the Summit) would be our only record of success. It was now 4:30PM, and daylight was fading fast. We quickly got to work descending, for we knew that it was of critical importance to navigating the steep sections of the peak before sundown. In the beginning, descending proved more difficult then going up. Downward momentum and plunging steps caused me to sink deeply with nearly every foot placement. Seeing this, Mike became concerned and expressed a need for increased speed. I agreed and decided to get into a sliding position in order to distribute my weight more evenly over the snow.

This method picked up the pace substantially and we began to make good time. Sean did the same in some areas, but Mike not having waterproof clothing stayed on his feet. As we neared the lower area of the summit plateau, Mike sped ahead in an effort to locate our exit point that would lead into the class 3 cirque as soon as possible. Sean became alarmed, however, when he saw Mike descending beyond what he believed to be the correct exit point. Checking his altimeter, Sean discovered that the notch was only seventy feet below his current position. He yelled this information to Mike and I repeated it, but the noise of the wind confused the message and instead of Mike hearing seventy feet, he mistook it for a hundred and seventy feet. This error caused him to continue his search further down slope.

I also believed the notch to be further down, and persuaded Sean to continue another hundred feet closer to where Mike was searching. Sean followed, but soon began to argue that we should turn around and go back up. I disagreed, and tried to talk him into descending a little further, but Sean refused. He then pulled out his GPS in order to get a definite fix on our position.

I also believed the notch to be further down, and persuaded Sean to continue another hundred feet closer to where Mike was searching. Sean followed, but soon began to argue that we should turn around and go back up. I disagreed, and tried to talk him into descending a little further, but Sean refused. He then pulled out his GPS in order to get a definite fix on our position.During that time I continued to descend but soon came to an abrupt halt when I saw him heading back up slope. Knowing that his instrument must have given him the exact way off the plateau caused me to change direction and rejoin him. Mike, who had been working independently below soon came to the same conclusion and quickly climbed back up to join us.

All this fiddling around had cost us, and the return to base camp was no longer a safe possibility. The absence of daylight and the steep chute below had eliminated that option. We quickly found an area where the snow was only about a foot deep and began to clear it. The three of us had gloves but Mike's had the fingertips cut out for climbing purposes. This made for cold work, but in spite of cold hands, the three of us were able to clear a four foot by six foot section. We pilled the snow on the windward side hoping that it would provide some protection from the wind.

Even at this point I was confident that all would go well. Throughout the day I was not just warm but actually hot, even while stopped to rest. I felt quite satisfied with our accomplishment and reasoned that a forced night out was just part of the adventure. Unfortunately, this nice little adventure of ours was about to take a serious turn.

Even at this point I was confident that all would go well. Throughout the day I was not just warm but actually hot, even while stopped to rest. I felt quite satisfied with our accomplishment and reasoned that a forced night out was just part of the adventure. Unfortunately, this nice little adventure of ours was about to take a serious turn.The wind was picking up, and without the sun, nature's thermostat was soon to be set at sub freezing temperatures. Not wasting any time, Mike and Sean unpacked their lightweight bivy sacks and I unpacked my little space blanket. Our plan was to fasten the two bivy sacks together and use the space blanket for extra insulation. The plan sounded good, but proved to be impossible.

The size of the bivy sacks and the fastening systems were not designed for such an arrangement, so plan "A" was scuttled. At this point, we quickly put plan "B" into action. Mike and Sean were to use the bivy sacks in the outer more exposed positions, and I was to be placed in the center with the space blanket. This would enable me to take advantage of the human wind barriers on each side.

Confident with this configuration, I figured the worst would be a sleepless night out. But my confidence quickly evaporated due to lack of activity and below freezing temperatures. Wind speeds continued to increase and airborn snow blew into every exposed crack of my clothing, and eventually ripped my space blanket making things even worse. Mike did what he could to help me rearrange the space blanket, but the wind had the upper hand, and shivering became the only means of maintaining body warmth. Mike’s single layer of fleece and marginal bivy bag also proved inadequate and he began to shiver too. Sean on the other hand was doing fairly well. His multiple layers of clothing and bivy sack provided excellent warmth. Good thing, because if anything happened to him, I would have to answer for it. I had talked him into this whole thing, and any injury to his person would be very difficult to live down, if ever. Mike and I on the other hand were in for a difficult night out.

I looked at my watch a couple of times, but decided early on not to make a habit of it. I remember checking the time every few minutes while spending an uncomfortable night out on the summit of Mt Whitney years ago. That constant checking of time made five minutes seem like an hour. So I figured I would wait for the emerging sun as a source of encouragement. In the meantime, Mike prompted us to breathe into our clothing and wiggle our toes. He believed this would enable us to maintain some degree of warmth and circulation.

I looked at my watch a couple of times, but decided early on not to make a habit of it. I remember checking the time every few minutes while spending an uncomfortable night out on the summit of Mt Whitney years ago. That constant checking of time made five minutes seem like an hour. So I figured I would wait for the emerging sun as a source of encouragement. In the meantime, Mike prompted us to breathe into our clothing and wiggle our toes. He believed this would enable us to maintain some degree of warmth and circulation.The suggestions proved somewhat useful, but any benefits were short lived. We had too many holes in our armor, and the wind found them all. As the night progressed, the cold continued to work especially hard on my feet, and because of this, there came a time when I could no longer wiggle my toes. This development brought to mind the possibility of frostbite and I mentioned it to Mike, but being half asleep he didn't answer.

Toward the end, I too fell asleep, but was shortly awakened by the dawn of a new day. I was first up, and quickly grabbed my camera to take some photos, but no camera and certainly no words could capture or describe the desolation and beauty of the northern slopes of Split Mountain in those early morning hours. Mike's and Sean's occupied bivy bags (shown in the photo above) only added to the barrenness of the scene.

The note below describes the conditions of the bivouac:

The note below describes the conditions of the bivouac:I figured that our air temperature based on Tom's readings of "25-28 degrees F" at Red Lake put us at about 15 degrees F at 13,000 Feet. According to a wind-chill chart, a wind of 15mph, which I conservatively figured we had, puts our real life temperature at minus 11 degrees F, according to the old wind-chill chart, or 0 degrees F according to the new chart done recently.

Scientists in Canada who did this research say that exposed skin at those temperatures can freeze in 30 minutes or less. Their research was done near sea level. High altitude and the effects of less oxygen make cold impact on the body even more severe.

Men on Mt Everest say that breathing oxygen from auxiliary tanks greatly warms the body. Therefore, lower elevations with more available oxygen are a great help to the human body when it comes to warmth. The Lord was merciful to us, for as Mike suggested: "If the temperature had dropped another ten degrees, the outcome may have been far more disastrous."

Not long after taking the pictures, we gathered our gear, and began the final descent to base camp. Doing so brought new life to my frigid limbs and I began to feel much better. I calculated that total success was only a few short hours away. The warmth of the new day had encouraged us all. We quickly found the notch, and began to descend the steep chute.

Not long after taking the pictures, we gathered our gear, and began the final descent to base camp. Doing so brought new life to my frigid limbs and I began to feel much better. I calculated that total success was only a few short hours away. The warmth of the new day had encouraged us all. We quickly found the notch, and began to descend the steep chute.Progress was excellent and Sean and I were able to slide down several sections. Mike followed behind on foot while taking some photographs. At the base of the chute, conditions deteriorated, and the snow seemed worse than ever. I sank nearly to my chest a few times and literally had to roll myself to the surface in order to extricate the lower half of my body. We finally reached the edge of the bowl and were able to look down and see Tom and Matt working their way up. We quickly joined them and all returned to camp.

I thought the worst was over, until I took off my boots and socks and saw my severely blistered toes that were hidden within. I knew the raised skin was not caused by abrasion because it was not located at traditional wear spots. Tom immediately recognized the blistered areas as frostbite, and upon hearing this, I suggested that he and Mike check out my medical manual to see what could be done for immediate first aid measures. After reading the short section on frostbite, they decided that very little could be done other than splitting up the weight I was carrying. Walking out empty would certainly minimize any further damage to my feet.

I thought the worst was over, until I took off my boots and socks and saw my severely blistered toes that were hidden within. I knew the raised skin was not caused by abrasion because it was not located at traditional wear spots. Tom immediately recognized the blistered areas as frostbite, and upon hearing this, I suggested that he and Mike check out my medical manual to see what could be done for immediate first aid measures. After reading the short section on frostbite, they decided that very little could be done other than splitting up the weight I was carrying. Walking out empty would certainly minimize any further damage to my feet.The final trek off the mountain went well, and the lack of feeling in my feet made travel pain free. We reached the vehicle in excellent time, and after loading the packs back in the vehicle, we made our way back to the main highway. From there, Mike took me directly to Lone Pine hospital for medical attention. I was taken in right away and the attending doctor confirmed the diagnosis of frostbite. They promptly put me on an IV containing antibiotics and fluids. This was done to prevent infection in the frostbitten areas and to combat dehydration that was brought on by inadequate fluid intake during the climb. Tom was with me during these early stages and noted all that was going on. The rest of the group waited outside.

I was hoping for a quick release, but this was not to be. Concerned about gangrene, the doctor admitted me to the hospital for further observation and treatment. His concern was over my right big toe which had turned dark blue. This information was relayed to the others, and shortly after, they decided to leave for home. I then called my wife and told her of all that had happened. Certainly, the call was not good news for her, but she took it well, and had faith that all would turn out well in the end. The stay in the hospital was deluxe compared to the previous night out, and the staff was very nice.

I was hoping for a quick release, but this was not to be. Concerned about gangrene, the doctor admitted me to the hospital for further observation and treatment. His concern was over my right big toe which had turned dark blue. This information was relayed to the others, and shortly after, they decided to leave for home. I then called my wife and told her of all that had happened. Certainly, the call was not good news for her, but she took it well, and had faith that all would turn out well in the end. The stay in the hospital was deluxe compared to the previous night out, and the staff was very nice.

I learned from talking to one of the nurses that mountain injuries were not uncommon, and that rescues take place nearly every year. The experience in the hospital reminded me of how personal people are in small towns. In the morning, my feet were given medicated whirlpool treatments that helped bring some feeling back into them. Next, it was decided that I should be transported to a Kaiser Hospital (where I had insurance) near my home. Arrangements were made, and shortly after lunch, I was off.

The ambulance ride to Los Angeles went smoothly and in hindsight, seemed like an-overkill. Late that afternoon I was admitted to the above mentioned hospital where I received further treatment for the next few days. Thank the Lord no toes had to be amputated. It has now been over two years, and I have regained only 50% feeling in the six toes that were affected. Most likely, full feeling will never return. Summit Fever had cost me and I certainly learned a lesson from it. Giving up the summit is always preferable to risking life and limb. I always knew that, but it is amazing how I could let myself get so carried away with the moment. Summit Fever is intoxicating for the Mountaineer, and it must be resisted when it comes to taking unnecessary risks. The mountain will always be there, the question is......will the climber exercise good judgment so that he or she will be able to climb again?

I was hoping for a quick release, but this was not to be. Concerned about gangrene, the doctor admitted me to the hospital for further observation and treatment. His concern was over my right big toe which had turned dark blue. This information was relayed to the others, and shortly after, they decided to leave for home. I then called my wife and told her of all that had happened. Certainly, the call was not good news for her, but she took it well, and had faith that all would turn out well in the end. The stay in the hospital was deluxe compared to the previous night out, and the staff was very nice.

I was hoping for a quick release, but this was not to be. Concerned about gangrene, the doctor admitted me to the hospital for further observation and treatment. His concern was over my right big toe which had turned dark blue. This information was relayed to the others, and shortly after, they decided to leave for home. I then called my wife and told her of all that had happened. Certainly, the call was not good news for her, but she took it well, and had faith that all would turn out well in the end. The stay in the hospital was deluxe compared to the previous night out, and the staff was very nice.I learned from talking to one of the nurses that mountain injuries were not uncommon, and that rescues take place nearly every year. The experience in the hospital reminded me of how personal people are in small towns. In the morning, my feet were given medicated whirlpool treatments that helped bring some feeling back into them. Next, it was decided that I should be transported to a Kaiser Hospital (where I had insurance) near my home. Arrangements were made, and shortly after lunch, I was off.

The ambulance ride to Los Angeles went smoothly and in hindsight, seemed like an-overkill. Late that afternoon I was admitted to the above mentioned hospital where I received further treatment for the next few days. Thank the Lord no toes had to be amputated. It has now been over two years, and I have regained only 50% feeling in the six toes that were affected. Most likely, full feeling will never return. Summit Fever had cost me and I certainly learned a lesson from it. Giving up the summit is always preferable to risking life and limb. I always knew that, but it is amazing how I could let myself get so carried away with the moment. Summit Fever is intoxicating for the Mountaineer, and it must be resisted when it comes to taking unnecessary risks. The mountain will always be there, the question is......will the climber exercise good judgment so that he or she will be able to climb again?

Deeper Insight - Summit Fever / Tunnel Vision

Conditions were poor for a summit bid on Split Mountain that day, but we decided to continue anyway. I of course (and I am sure Mike and Sean also) wanted to make it off the summit plateau before sunset, but felt very confident that if necessary, we could spend the night out without any mishap.

Isn't that the way it is spiritually at times. Too often we invest time and energy into some area of our life that is either outside of God's will, or not within His timing. We end up pushing ahead anyway, and end up paying a steep price for our efforts.

Isn't that the way it is spiritually at times. Too often we invest time and energy into some area of our life that is either outside of God's will, or not within His timing. We end up pushing ahead anyway, and end up paying a steep price for our efforts.

When a mountain climber gets summit fever tunnel vision sets in, and danger signs go unheeded. "Summit Fever" had definitely clouded my decision making ability that day, and if this were not bad enough, I encouraged my son Sean to join in against his better judgment.

I had become so driven, that even after making the summit, I failed to make early use of the instruments that Sean was carrying. (GPS and Altitude Watch) So often, we get single minded when it comes to our own agenda, and try to get others to join in our folly. We fail to check God's Word, the ultimate instrument for guidance, and end up paying a big price. When we get into this pattern, we need to stop and take time out to check the guide book. Only in this way, will we be able to determine what we should do. His Word will tell us if we should go on, or turn around (repent). If we fail to do this, unwelcome consequences will certainly come our way.

Galatians 6:7 "God is not mocked: for whatever a man sows that shall he also reap." If we ignore clear warning signs of impending danger, we can only look to ourselves for blame when things do not turn out well. And sometimes.....we just need to wait. We should have turned back, and waited for better conditions. Tom, who did not make it to the top that day, returned later on and easily made the summit under dry conditions.

Galatians 6:7 "God is not mocked: for whatever a man sows that shall he also reap." If we ignore clear warning signs of impending danger, we can only look to ourselves for blame when things do not turn out well. And sometimes.....we just need to wait. We should have turned back, and waited for better conditions. Tom, who did not make it to the top that day, returned later on and easily made the summit under dry conditions.

Isaiah 40:31 tells us that: "they that wait upon the LORD shall renew their strength; they shall mount up with wings as eagles; they shall run, and not be weary; and they shall walk, and not faint." We need to remember this verse, when we are tempted to go forward when God tells us to wait. God's timing is always best.

Finally, if we are to become fixated on anything, or be driven to the point of summit fever, let us make sure we are on the right mountain. The base of that mountain is called Calvary. That is where Jesus Christ paid the price for our sins. We cannot even get on the lower slopes apart from His finished work on the cross. From there, we need to start up the slopes. It's a lifetime journey, but summit fever on this mountain is a good thing, because it leads to a day when we shall be with the Lord forever.

So in the meantime, as we work our way up the slopes, let us be of the same mindset as the Apostle Paul:

Philippians 3:12 "Not that I have already obtained all this, or have already been made perfect, but I press on to take hold of that for which Christ Jesus took hold of me."

Press on fellow traveler, the summit is just coming into view,

Dave French

Conditions were poor for a summit bid on Split Mountain that day, but we decided to continue anyway. I of course (and I am sure Mike and Sean also) wanted to make it off the summit plateau before sunset, but felt very confident that if necessary, we could spend the night out without any mishap.

Isn't that the way it is spiritually at times. Too often we invest time and energy into some area of our life that is either outside of God's will, or not within His timing. We end up pushing ahead anyway, and end up paying a steep price for our efforts.

Isn't that the way it is spiritually at times. Too often we invest time and energy into some area of our life that is either outside of God's will, or not within His timing. We end up pushing ahead anyway, and end up paying a steep price for our efforts.When a mountain climber gets summit fever tunnel vision sets in, and danger signs go unheeded. "Summit Fever" had definitely clouded my decision making ability that day, and if this were not bad enough, I encouraged my son Sean to join in against his better judgment.

I had become so driven, that even after making the summit, I failed to make early use of the instruments that Sean was carrying. (GPS and Altitude Watch) So often, we get single minded when it comes to our own agenda, and try to get others to join in our folly. We fail to check God's Word, the ultimate instrument for guidance, and end up paying a big price. When we get into this pattern, we need to stop and take time out to check the guide book. Only in this way, will we be able to determine what we should do. His Word will tell us if we should go on, or turn around (repent). If we fail to do this, unwelcome consequences will certainly come our way.

Galatians 6:7 "God is not mocked: for whatever a man sows that shall he also reap." If we ignore clear warning signs of impending danger, we can only look to ourselves for blame when things do not turn out well. And sometimes.....we just need to wait. We should have turned back, and waited for better conditions. Tom, who did not make it to the top that day, returned later on and easily made the summit under dry conditions.

Galatians 6:7 "God is not mocked: for whatever a man sows that shall he also reap." If we ignore clear warning signs of impending danger, we can only look to ourselves for blame when things do not turn out well. And sometimes.....we just need to wait. We should have turned back, and waited for better conditions. Tom, who did not make it to the top that day, returned later on and easily made the summit under dry conditions.Isaiah 40:31 tells us that: "they that wait upon the LORD shall renew their strength; they shall mount up with wings as eagles; they shall run, and not be weary; and they shall walk, and not faint." We need to remember this verse, when we are tempted to go forward when God tells us to wait. God's timing is always best.

Finally, if we are to become fixated on anything, or be driven to the point of summit fever, let us make sure we are on the right mountain. The base of that mountain is called Calvary. That is where Jesus Christ paid the price for our sins. We cannot even get on the lower slopes apart from His finished work on the cross. From there, we need to start up the slopes. It's a lifetime journey, but summit fever on this mountain is a good thing, because it leads to a day when we shall be with the Lord forever.

So in the meantime, as we work our way up the slopes, let us be of the same mindset as the Apostle Paul:

Philippians 3:12 "Not that I have already obtained all this, or have already been made perfect, but I press on to take hold of that for which Christ Jesus took hold of me."

Press on fellow traveler, the summit is just coming into view,

Dave French